New memoir in its entirety. Still looking for right agent. Meanwhile, enjoy!

Hallelujah! The New York Times has OK'd women getting pissed off. "Women Writers Give Voice to Their Rage." A raft of books, both fiction and nonfiction, examined women's anger from personal and political angles--and suggested that the fire is just getting started.The fire has been burning forever, you stupid New York Times, try as you have to throw blankets of scorn over us when we got as mad as men. Mad Women Matter.

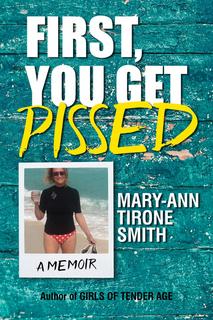

And so, very dear readers, I hope First You Get Pissed strikes a chord the way Girls of Tender Age did. (Please note the Sally Fields epigram I chose for this book.)

DEDICATION

For Leroy Hommerding, Director of Beach Library, Fort Myers Beach, FL, who took me under his wing, recommended my first memoir Girls of Tender Age to the library book club, and then invited me to lead a discussion when the book was scheduled. He came to the discussion, took a chair with the book clubbers and blended in. (This was not unlike Caesar blending in at the Forum.) Dr. Hommerding showed me a desk in the library where I could work, with a window to the horizon, no distractions, nothing but the Gulf of Mexico. With that, I knew I was home. Thanks Dr. Hommerding.

Leroy C. Hommerding

October 20, 1949--February 20, 2019

Rest in peace, precious friend.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Amanda, Joey, Emmie, and Chris Borst, Jene Maria Smith, Jere Paul Smith, Kim Gonzaga, Duane Trevail, Tadhg Hoey, Marnie Mueller, Karen E. Olsen, Betty Rollin, Joan Schmitz, Barbara Tirone, Marion Morra, Eve Potts, Laraine Olinatz, Heather Styckiewicz, the staff at Beach Library, Fort Myers Beach, Florida, and in memory of Mollie Donovan and Shirley Temple Black.

How long would it have taken me to feel that I had a right to be out outraged?— Sally Field, In Pieces

Chapter 1.

THIS YEAR, this summer, the first week of August, I get a phone call. Caller ID reads: Yale-New Haven Hospital. I figure it's my daughter Jene, who probably has to use a company phone since there's no cell service in her neck of the hospital, Infectious Disease Medicine, where she's a nurse. A woman's voice, not my daughter's, answers. "Hello, I'm Dr. Somebody." Her name doesn't sink in because I'm experiencing an immediate loss of breathing ability, thinking that something's happened to Jene. Then the voice says, "I'm a radiologist at Yale."

"Fuck," I say, but in a whisper, and I hold my cell up away from my mouth. I'm figuring Jene broke her arm, as if she's seven years old when she did break her arm. When upset, I ordinarily say to myself, shit. But this is a far higher grade of upset. There are times when dropping the F-bomb is therapeutic.

Before I can ask the radiologist what happened to Jene, she says, "We've seen an anomaly in one of your images. It almost always means nothing, but we still want to do a second mammogram. My nurse will make an appointment. I'll connect you."

She said something else, maybe including goodbye, I wouldn't know. What's important is Jene doesn't have a broken arm, even though some doctor has just pushed me off a cliff. I hear the phone beeping, making its connection, while the radiologist's words that I did grasp, begin bouncing off the sides of my brain: It almost always means nothing. That would be bullshit. The giveaway, meant to soften the blow but of course having the opposite effect, are the two words, almost always. Almost always is not nothing.

I'm switched over to the nurse. I don't remember the appointment conversation with her, but I know I made one because I put the date in my cell, August 22nd, though I don't remember doing that either. What I have is a flash of a different memory altogether: Once, after a previous mammogram, while I was getting dressed, the technician reappeared. The johnny-coat, size C (colossal), had fallen around my ankles and I'm trying to step out of it. She gave me a big smile.

"I'm so sorry, Mary-Ann, I need another picture. Something seems awry with your left breast. I'm sure it's because you moved."

I moved? Does one dare to move when one's breast is in a vise?

I get a second round of torture. The verdict: "My error. There was nothing there."

I say, "Thank you."

I already thanked her for torturing me the first time, but if you have my mother for a mother and you have to say please and thank you every other minute or you're a sociopath.

But skipping to today, this beautiful summer day in August, I've got an unknown radiologist on the phone, telling me something is awry. This is not a technician; it's a doctor. It's something, not nothing, for sure. But all I know is I have to talk to Charlie. Charlie is my husband. Before he was my husband he was a widower. His late wife died of breast cancer.

Fuck.

I will wait for the right moment to bring this up with him, but as any shrink will advise—say you have to inform the kids you're getting divorced—there is no right moment, even if you follow up with, "Look! I've got Southwest tickets for April vacation. We'll go to Disney!" (Though that only works if you're Ben Affleck and Jennifer Garner.) I know I am just going to have to spit it out.

I pour myself an afternoon glass of pink wine from Provence and take it out on the deck. I live on Long Island sound, compliments of An American Killing, my fifth novel. Charlie is out on his boat with a friend from the marina fishing. I think about my breasts. They're beautiful. They make me feel good about being a woman; they please Charlie while he's pleasing me; and they allowed me to luxuriate in that unique intimacy between two humans—me and my newborn—she chugging down breast milk like it's a Sam Adams.

When Charlie comes home I can't face up to spitting it out yet. He's all excited about the fish he's got in a bag of ice. He says to me, "We're having the greatest piece of flounder for dinner. So big, I gave half the filet to Mike. Want to see it?"

No, but I say, "Yes." Then I say, "He's a beauty."

"So how about your mother's favorite drink?

"Sounds good." Nothing sounds good.

He stashes the fish and makes us two sidecars. He carries a tray out from the kitchen—two sidecars and beer chasers, speaking of Same Adams, just the way my mother used to drink them. He asks, "How'd it go? Hurt a lot?"

"Yes."

He puts the tray down, "Sorry, honey." He takes me in his arms. A very delicate hug. Then he looks down at me. "Let's go outside. Sit on the beach."

He hands me the tray and grabs two chairs. I have always aspired to be a beach bum. And here I am. Sipping my sidecar, I'm acting cheerful as if it's just any old day, because I need to enjoy a little denial, a gift from the gods, don't you think? At least when it doesn't put you in jeopardy, like putting off a root canal till you're having a horrific, throbbing toothache and it's a Sunday.

Here is the main difference between gazing out at an ocean and gazing out at Long Island Sound. The ocean has crashing waves and the occasional freighter. On the Sound all is serene: vessels of every every sort, from decrepit dinghies to flying cigarette boats, make trails across the surface; lobster markers bobbing; kayakers paddle; kids in a rowboats reel their rods in and cast, over and over; there's a glimpse of Long Island cliffs on the horizon; and birds, birds, birds. (I once had a stringer from The New York Times come to do an interview for the Connecticut section. It was a good article except for her mentioning how I could watch pelicans from my office window. They were osprey. And yes, you heard me right—The New York Times.)

So we head back inside and Charlie grills his fish. The man cooks. He is a good cook. We start with the mussels picked up at the fish market; they're lolling in front of me in white wine and garlic and butter. Also, French bread he had to go five miles out of his way for. He's poured Sauvignon Blanc. I'm tipsy from the sidecars. I've given over almost entirely to denial. The radiologist was reading someone else's images, not mine.

I still have to tell him. First, we watch the Sox game. A win. Nice. But then I'm brushing my teeth, chanting silently to myself: There is no right moment, there is no right moment,there is no right moment. Can you brush your teeth all night? I press the button on my electric toothbrush, put it back into its stand, screw the top onto the toothpaste, and look at myself in the mirror. (I paused between each of those steps.) Then I say to my face, "Get it over with." My usual flossing and the rinse of Listerine will have to wait.

As soon as I come into the bedroom, our dog Salty departs his first choice as to where he prefers to sleep—in my spot with his head on my pillow—and scoots to the foot of the bed. He performs this ritual every night. It's great in winter since his 58-pound self leaves me a big warm spot. Salty will remain at the foot of the bed until he's sure we're asleep. Then, ever so cautiously, he'll make his way back up the edge of my side of the bed, where he will stretch out next to me and plant his head on my pillow once again, which is why I need a king size pillow: Presto—blissfully unconscious. I sleep between man and beast.

Tonight, though, I stand there gazing at Salty before I climb in; he doesn't know why. He raises his shaggy Labradoodle head, and I scratch him behind his ears. I get in, making my way around him, and nestle into Charlie's chest; a magnificent chest, I have to say—he's got broad, hard muscles, his chest is gently hairy, and he has especially sexy nipples. Neither of us has put on a pair of pajamas since the first time we co-mingled. We are diehard cuddlers what with being naked every night. We entwine our naked selves together like two kittens and pretty much make love without thinking twice. But tonight….

"Sweetheart?"

"What, baby?"

"I have to have another mammogram. They saw what they called an anomaly, but the doctor said it almost always means nothing. I'm sorry." Somehow, I think of Nancy Reagan, who told the president she was going to have a mastectomy and that she was sorry. At the time, I thought she was apologizing because he would have a wife with only one breast, but now I realize she was saying she was sorry because they had to face something unbearable, mainly to her.

Charlie's breathing stops just like mine had when I heard the almost always thing. He knows from almost always. I wait. When he can speak, he calmly asks, "Have you felt a lump?"

"No."

"Me neither." Considering the way his first marriage ended, he's obviously been on guard.

Charlie passes into a mode of being there for me. He props himself up on his elbow. "You're going to be all right. Even if there is something, it's very soon. I mean, we still can't feel anything."

We.

He pulls me into his strong arms and says, "I love you."

Charlie has a fabulously deep voice. When he says, I love you, it's as if the words are coming from a sound chamber in his soul. When I met Charlie, I said to my friend, the writer Sarah Clayton, "He has this really deep voice," and she said, "A deep voice goes a long way."

So then we're nuzzling, we're kissing, we're touching each other all over. Making love. It's our best way to communicate; Charlie has had a fairly serious hearing loss from the time he was a kid. He didn't get medical attention for chronic ear infections until they became mastoid infections. The mastoid is the bone behind your ear. Can you imagine that getting infected? His widowed mother was "on the dole." That's what welfare was called back in the day. When my friend the writer Katharine Weber was five, she told her parents she couldn't see out of one eye. She didn't get medical attention either, even though they had a ton of money. They just wouldn't believe her. She was born blind in one eye and no one noticed. Talk about denial.

But meanwhile, re Charlie, let me tell you this: I would rather have a man who can't hear me than one who won't listen to me. I know from both.

Chapter 2.

WHEN AUGUST 22nd arrives, I'm back where I don't want to be—back at the imaging center at Yale-New Haven Hospital. I'd rather be in an opthamologist's office having glass shards picked out of my eyeballs. Charlie has been ushered into a special waiting room for family and friends of women having advanced placement mammograms. Salty is enjoying the action at doggie day care.

I wait and wait. The night of that first mammogram, I woke up at two in the morning, tossing and turning, which woke Charlie up. He rubs my back. He asks, "Did the radiologist say if it's Starlight or Starbright?"

"If she did, I wasn't paying attention."

Once, when looking at my breasts after bestowing them with his sweet caresses and warm kisses, Charlie said, "I love you, Starlight, and you too, Starbright. You're gorgeous." Charlie gave my breasts names. And unlike the usual names for body parts, they're pretty names, terms of endearment, unlike "tits" and "hooters" and "boobs"—or with the opposite gender, "prick" and "dick" and "nuts." If I hear cunt, I emotionally gag. John Updike once described nipples as doorbells. That made a lot of people laugh—men who actually hate women, and women so used to denigration they hate themselves.

(An aside to cheer you up after that last: My friend, the writer Liz Livingston, had a dog named Willy. Her husband got transferred to London and Willy got to go, otherwise the children would have chained themselves to the back porch. The wives of her husband's new colleagues invited her to tea. One of them said, voice hushed, "I have to tell you something a tad embarrassing. The name Willy— in the patois, shall we say?— means penis." And Liz said, "That's all right. My husband's name is Dick.")

By the way, the wives didn't get it.

After the little back rub, I turn to Charlie and he starts making out with my breasts. He says, "Your breasts give me peace, Mary-Ann. Make me feel calm, ya know? You'll be okay, I know it." Then he gets a little weepy. He such a tender guy, him and his deep voice.

I said, "All I know is, you are really making my toes tingle."

He stopped being weepy and gets turned on instead.

Not so long afterwards, wrapped up in one another, Charlie and I both pretend to fall asleep, until we finally and blessedly, somehow, do. Only then does Salty move up the bed and into position on the other side of me, snuggling up more closely than usual. He knows all is not well.

This reverie carries me through waiting for my second mammogram, until my name is called. I meet up with my technician in the room with the mammogram machine, all revved up and ready to go. But this time, the two steel plates are a quarter the size of the usual ones, about like two slices of Pepperidge Farm bread. Incredibly, the technician says to me, "The plates are geared to sandwich only your breast anomaly."

She arranges Starbright on the bottom plate. In my denial state, I never called the radiologist to find out which breast had the anomaly; now I know. She has me hold the bar alongside the machinery. She dashes over to a console, presses a button, and the upper plate descends. When Starbright is hurting, she returns to my side and lowers the upper plate manually with a twist of a short rod sticking out of the side of the machine. I am gripping the bar with all my might, tears springing to my eyes.

"Can you take another turn?" she asks me.

"NO," I shout. "I MEAN IT!" Did you read A Prayer for Owen Meany by John Irving? Irving has Owen speak in caps, he's so LOUD! Italics—even with an exclamation point—won't cut it. I think the operatic velocity value fff—meaning triple fortissimo—would not do Owen's voice justice either, that's how effective Irving's talent is for characterization. He took advantage of poetic license because he decided he would find a way to out-do himself. All readers loved it excluding reviewers, naturally.

Owen Meany's voice was necessary for me to demonstrate my determination to be taken with utmost seriousness since the last time I got that question: Can you take another turn? No didn't mean NO! I took a page from Owen. It worked. Instead of another turn, the technician dashes around to her control panel, calling out to me, "I'll be really fast." I grip the bar even more tightly, bearing the singular pain of a breast crushed between steel plates. She calls out, "Three seconds, two seconds, one second, done!"

Starbright is released.

She rushes over to me. "You okay?"

"I'm not."

"I'm really sorry."

I can tell she is. "I appreciate your running."

She's not finished, naturally. I forget all about the dreaded side view, but it doesn't hurt any worse than the usual side-view mammogram, don't ask me why. It doesn't take as long, either, thank God for something. I only know it's over. The technician tells me I can get dressed.

Have you noticed how no one asks you your pain level when you have a mammogram? My average is 8. With this ultra-mammogram, it's a 10. I once complained to someone about dreading mammograms, and she said, "It doesn't hurt that much," meaning, Oh don't be such a baby. What is wrong with this picture? Answer: Everything. There's nothing whatsoever right about being treated like an asshole when you need TLC, as with, for example, I'm sorry. It's so unfair, I know. But at least it's once a year, not once a week. Notice in the example I just gave I didn't precede once a year with only since, again, I'm talking TLC here.

So after getting dressed, as I'm about to grab my bag to leave, the technician has one more thing to say and it's not, "Bye." She says, "The doctor will be out shortly."

I ask, "What doctor?"

"The radiologist. The one who called you. She's looking at the images now."

"How come?"

"She's comparing them to last year's. She's in her office." She points to a door. It's next to another door that is my now-elusive escape hatch. "She'll be right out. Have a seat."

My stomach turns over. I sit down on a little bench for one set against the wall. I feel like I've committed a crime and the jury is out. I don't care if I have to wait a really long time—all day—so what? Because when the jury walks out and is back before you have time to blow your nose, forget it, you're guilty. Five seconds later, the jury door opens.

A tall, slim, very pretty girl in a lab coat who looks to be in the neighborhood of twelve years old comes right over to me, smiles and puts out her hand. So do I. I'm trying to smile, but doubt if I'm successful. We shake.

"I'm glad to meet you, Mrs. Smith."

Mrs. Smith is my late mother-in-law's name.

She next says, "I'm Doctor…" She tells me her name, and it goes in one ear and out the other just like before on the phone. My brain has made an executive decision: If you don't know her name you'll think you're dreaming this whole damn thing.

But this is no dream, you stupid brain. This is the opposite.

Dr. Whatever steps over to a chair and pulls it up to where she can sit down and face me on my bench. She's Asian. But this is Yale. You might as well be in Beijing. She looks deep into my eyes, and asks, "Do you mind if I call you Mary-Ann?"

I say, "I'd rather you do." I do not ask, Do you mind if I have no idea what your first name is, or your last name, because I don't want to know?

She says, "I'm the doctor who spoke to you on the phone."

We are not even a foot apart; I can feel her breath on my face. I also feel my saliva drying up so I try to brace myself. I don't want to faint, fall off the chair and have a concussion, although I surely would rather have a concussion than listen to whatever the thing is she's going to tell me.

She leans another half inch closer. She looks even younger up close, like she must be one of those brilliant kids with a tiger mother who sees to it that she graduates from high school at nine.

She becomes chummy. "Ya know, Mary-Ann…see…. Well, like, here's the thing." She sighs. It is a sigh of sympathy. That's nice. Carefully, as she has chosen words that will not sound doctorly but rather sympathetic, she says, "We have, like, loads and loads and loads of ducts." I think she said "ducks." Maybe she is nine…maybe she skipped elementary school altogether and still got into Yale. She continues."I mean, like, we have…" then, her voice goes up a couple of decibels though nowhere near Owen Meany's "…a zillion ducts!"

Ducts. This is not good.

"We have bile ducts! We have lymph ducts! We have intrahepatic ducts…" She gives me several more examples of ducts I've never heard of, finishing with one I have, "…and we have mammary ducts!"

My brain starts playing my favorite comfort song, the first song I remember, "My Blue Heaven." My father used to sing it to me at bedtime. In preparing for my father's funeral, I included the song in my music list. Paul, the organist, calls to tell me the priest won't allow it. I call the priest. He says, "Secular songs are inappropriate. That one is not about Heaven."

The church is in the Irish neighborhood in Hartford, CT, where I was born. I say to the priest, "I know it's a secular song." (I don't say, And I know it's not about Heaven, you nitwit.) Instead, I say, "'Danny Boy' is a secular song." Paul plays it all the time. The priest says, "People will think your father has a mistress named Molly." A line of "My Blue Heaven" goes, "Just Molly and me, and baby makes three…"

As with all Catholic hierarchy, the man is obsessed with avoiding scandal, a far greater sin than, say, a raping a child. Can you tell I'm pissed? Can you tell I was really close to my dad? His version of "My Blue Heaven": "…and Mickey makes three…" My nickname is Mickey. I didn't call the priest a hypocrite, though. I'm too civilized. And for sure, my father wouldn't have approved of me calling him a name, though he would have said to me, "Don't worry about it, little Mickey. The guy's a nitwit."

The radiologist has been interrupting this recovered memory throughout. I pick up, "Are you okay?"

"Sorry, excuse me. I'm having a hard time paying attention."

"Of course you are. Please try to concentrate. I want to tell you about the problem with ducts."

I come back to her. "Okay."

"Ducts are full of …JUNK!"

Good God, I thought she was going to say they were full of shit. The word JUNK, as you must know, did Owen proud.

Rather than respond to her with, Get to the point, since I don't want to know the point, I say, "My mother never let a day go by without telling me to get rid of all my junk."

"OMG!" (And to remind you the timbre is also known as fff.) "My mother too!"

What does one say to that, to this person, at this time, in this place where I'm trapped? Nothing. Besides, she's on a roll, doesn't leave me a second to respond to what our mothers have in common. "So…here's why our ducts are full of junk." (Good. She's toned things down and is still not getting to the point.) "Because when our cells die, they're replaced with new cells. But the old cells leave deposits behind... DEPOSITS!"

Oh dear, right? Turns out our ducts are full of shit.

She says, "And one such deposit is called…" (drum roll) "…a calcification!" She takes a big breath and keeps going. "But! We have calcifications throughout our bodies, not just in our ducts." (She's still emphasizing ducts but not so significantly.) "So! you can have calcifications anywhere, like…like…in your larynx. But calcifications in hard tissue, such as the larynx, are not a worry. They just sit there."

Here it comes, because who doesn't know breast tissue is soft? She's now speaking to the point, dropping the use of like as an adverb. I have no problem with the like since it's the equivalent of um. I think um is worse.

"So…" (No like, but she will still start off sentences with the conjunction so, sometimes more stongly than other times, which I do all the time, even though language purists will rant) "…last year, Mary-Ann, I saw a few teeny-tiny calcifications in one of your mammary ducts in the left breast. Calcifications found in mammary ducts can sometimes be the deposits of mutated cells. And sometimes the deposits—the calcifications—will form a pattern. I saw no pattern last year, and neither did my colleagues."

Is that good or bad? "However, when the next year rolls around, when the patient—you—has another mammogram, most of the time the calcifications are gone. Sometimes they're not. Sometimes they have even increased in number."

She pauses, waiting to see if I can take what's coming. Oh, but I can't. I already know it will be bad, what with the introductory conjunctive adverb, However. Do I have a choice though? No. I say, "My calcifications have increased, haven't they?"

"Yes." She reaches over and touches my wrist. "When you were here last week, I immediately took a look at that particular duct where I'd seen those few calcifications a year ago. Not only have their numbers increased, they've increased significantly, and the calcifications have formed a pattern."

Even though I knew she was going to say something terrible like that, at least her voice is growing softer. She is calmer, and no longer in need of like.

I ask, "A pattern? A pattern like a china pattern?"

"Uh…no. More like a cluster actually. The calcifications have formed a cluster, a little independent galaxy of their own."

I tune her out, though not deliberately. My brain, needing a rest, is stuck at galaxies. I love galaxies, along with constellations and meteor showers, and human-made satellites, and everything else in the sky. Once, my children and me, and their cousin Melanie, lay on our backs in a field behind the neighborhood elementary school, watching the Perseid meteors showering across the Milky Way. We tried counting the number of meteors in each shower. We didn't get far because Melanie threw up. Lying on your back and watching meteors zipping overhead can actually make you carsick if you are so disposed. Besides the Melanie episode, another time, at four o'clock in the morning, my son patted my shoulder. I woke up and he whispered in my ear, "Mom! The aurora borealis. Hurry."

I crept out of bed and followed him to the deck without falling down the stairs; God forbid we should wake up his dad by putting on a light, as with, "I have to go to work in the morning!"

Above the deck and the trees, the Connecticut sky was bursting with Technicolor striations. My son, whose name is Jere, would grow up to ask his beloved girlfriend to marry him, and how might she feel about having the ceremony during the upcoming Delta Aquarids? These are lesser known meteor showers, radiating from the constellation, Aquarius, in case you don't know. His girlfriend thought it was a capital idea. (I am profoundly grateful he found his Kim, who becomes our Kim during last year's Delta Aquarids.)

The radiologist notices how I'm drifting to a better place and lets me have my moment of peace. Then she has to interrupt again. I'm not her only patient, after all.

"Mary-Ann?"

I say, "Go ahead."

She tells me what I need to hear about the galaxy in my mammary duct, and I have to pay attention so I can tell Charlie the exact words. Right now he is waiting and waiting out in that higher-level waiting room, wishing for a shot of Macallan 12. I am wishing the same.

"This anomaly requires we check it out with a biopsy. But the good news—the way good news—is that the higher-resolution, limited-angle mammogram shows that no cells have made their way through the duct wall. I could see that none have become invasive."

I now feel my first emotion after a week of my nerves being shot. A ping of anger. I am picturing a bunch of scrawny-assed cancer cells joining forces to batter their way through the wall of my mammary duct so they can chow down on Starbright. I am as pissed as my brain.

I say to the radiologist, "The fucking little bastards."

The radiologist says, "Yeah. But remember, I didn't see any outside the duct."

Then, her elbow on her knee, her chin resting on her hand, she says, "A biopsy is the final word as to whether or not what I'm seeing is a lesion."

I do not skip a beat. I'm sick of it. "A lesion is cancer."

"Yes."

She really cannot stand saying the word "cancer." I'm thinking that when this poor woman must tell a patient cancerous cells have burst through her mammary duct—that she is seeing an invasive cancer—it breaks her heart. All I know is I can't stand saying the word cancer either. And now I have to prepare myself for accepting that the word applies to me.

She takes my hand and holds it very gently in both of hers. She says, "Let me describe the biopsy procedure for you."

Now, if you've never had a breast biopsy described to you, hang on to your hat. Better yet, smoke a joint. It's medicinal in this case because, like me, I'm sure you figure that a biopsy simply means someone sticks a needle into your breast and sucks out a couple of cells of junk from your duct to be sent out and examined by the boys in the lab. When I was a kid, I loved "Hawaii Five-O," who didn't? In every episode I remember, Jack Lord can be counted on to say two things to James MacArthur: "Book 'em, Danno," and "Send this to the boys in the lab," the latter when he's holding up a possibly blood-stained screwdriver.

But if you don't have a joint immediately available, go pour yourself a shot of Macallan 12, or if you don't drink, then have a mug of coffee unless you're a tea-drinker, in which case, brew the superb lapsang souchong. If you've never heard of it, alas, go with Lipton's or whatever, because you're sure as hell going to need something. I'll wait for you.

*I think recovered memory is a perfect term for a memory that hasn't crossed your brain since the event happened, until one day, it just does, triggered by something that is not necessarily traumatic. (To me, "traumatic" would infer a repressed memory; what I'm talking about here is a memory inadvertently deleted, but still hanging around in the trash bin.) I recover memories all the time, sometimes stirred up, for example, by the process of falling in love.

Capisce? Good. Because this book happens to be a memoir. Memoir is French for memory. I've been recovering a lot of them of late. Otherwise, I wouldn't have this book; I'd be doing the other thing I do—making stuff up. That would be fiction.

Chapter 3.

THIS IS WHAT a breast biopsy actually entails, as promised. Ready?

The radiologist starts with, "You'll be on your stomach on a table with a hole in it. Then—"

I interrupt. "I'm getting a massage first? That'll help."

"Uh…no. The hole is where your breast will hang through so we can do a much more intense mammogram, previous to—"

"Starbright will hang through a hole?"

"Who?"

I explain about Charlie's names for my breasts. She says, "That's so sweet." Then I repeat my question: "You're saying my breast will hang through a hole?"'

"Yes. Because if you were lying on your back, your breast would flatten over your chest and the challenge to the procedure would then require—"

"Never mind. I'll take your word for it. And where are you? Underneath the table? On one of those things your mechanic rolls around on under your car?"

"Not exactly…" she gets a rather huffy expression on her face, but right away reverts to her previous kindly demeanor. She has trained herself not to take offense with her patients. She says, "It's a stool. But it won't be me who's rolling around. Another radiologist will be on the stool, and a nurse and technician will scoot under the table as need be."

"They'll each have their own stool?"

"Yes."

What did I think? They'd be down on their hands and knees? Something suddenly occurs to me: "Are you saying you won't be doing the biopsy?"

"That's right."

"Why not?"

"What I do is analyze images."

"Oh."

I visualize three strangers crammed under a table with Starbright in the middle. I wonder how they get at the breast of a woman with perky little ones. At Branford Harbor, where we have our boat, there is a captain whose named her boat, Sea Cup, which is the size of her bra. I'm a Sea Cup, myself. When I told the captain that, she gives me a knuckle-bump. Charlie bought his boat before he met me. His daughter insisted he name it her own choice, the Already There, instead of his, Comfortably Numb. I guess she didn't want her dad to be associated with weed. Charlie always loved the Eagles. We went to their last concert before Glenn Fry died. One time, we passed a boat with a bunch of drunks on it, and someone yelled to us, "I'm glad you're already there because I'm nowhere."

Alas, I must force myself to concentrate on the business at hand, but I want very badly to blink like I Dream of Jeannie and vaporize, but can't. I have to listen as the radiologist continues along.

"First, the doctor will numb the breast... he'll numb Starbright, actually." She smiles at me. "Starbright won't feel anything at all."

We are very glad to hear that. I like this woman. I think upon hearing my breasts' names, she somehow feels sympathetic toward them as well as me.

"And next, he'll make a quarter-inch incision—"

"INCISION?" She pulls back, her ears probably ringing. I take a breath. "I'm sorry, but did you say incision?"

"Yes."

"Why would a needle require an incision? How the hell big is it?"

"It's not a needle."

"It's not? What is it?"

"It's a spring-loaded, large-core transducer. Essentially, a—"

"Excuse me?"

She clears her throat so that she can talk fast, preventing me from interrupting her again. "A transducer is essentially a metal tube filled with very fine needles with barbed ends…" I'm thinking, but do not say aloud, Jesus Christ Almighty "…and these barbs will hook several strands of tissue within the duct. Then the transducer will draw them out of the duct and into its tube. After that, the transducer is taken out. Then we send the specimens to the lab to see if the cells in the duct are cancer cells."

I feel tears coming to my eyes. I try to speak so I won't actually cry. I have questions that need answering. I swallow. "How will the other doctor get it out?"

"The transducer?"

"Yes."

"He'll pull it out."

"How many specimens will be in it?"

"Four or five."

Whew. I'm thinking she'd say eight hundred. "Will the incision require stitches?" Naturally, I know it will. I'm hoping for the same number of stitches as the specimens, or fewer. Imagine the number of stitches you need if you're breast is riddled with cancer.

She says, "Two…maybe three. Then we'll leave a marker behind—a tiny wire—so that if you do need to have surgery to remove the duct, the breast surgeon will know exactly where to go."

"There are surgeons who only do breasts?"

"Yes, but if you choose, you may have any surgeon you like, including one who doesn't specialize in breasts."

I feel a ping of anger again, this one immediately spreading out through my entire body. "What do I look like, doc, some kind of idiot?"

Her voice takes on a lecturely tone, "No, Mary-Ann. You don't. What I mean is, if you've had a surgeon in the past, you can talk to him or her about all this. You might decide that surgeon would be more appropriate." She puts her hand on my knee and smiles. "But if not, you will have the best breast surgeon in the country. We are so fortunate she is right here at Yale. Diane Quigley. I will see to it that your surgeon will be Diane Quigley."

I will never forget Diane Quigley's name. But I'm not ready yet for that particular discussion. I need to finish this one. "About the marker. You said it's a wire, right? How big is it?"

"It's the size of an eyelash. It will serve to guide the surgeon."

I try not to picture a doctor with a scalpel in each hand rummaging around inside my breast looking for an eyelash. The radiologist seems to know what I'm thinking. She says, "The end of the marker will stick out of your skin and there'll be a Band-Aid over it."

Can you believe this? I can't, but it's all true. Right at that moment, I do not want to know anything else about a wire eyelash sticking out of Starbright. I'm finding myself overwhelmed. I need to backpedal. I have to ask an extremely specific question centered on statistics. Statistics is truth. I don't like surprises. So here is my pressing question for the radiologist: "What are the odds that the calcifications are cancer?"

She doesn't skip a beat. "Twenty-five percent."

"Is that based on your own experience?"

"No. That's based on statistics."

I know exactly what she means by No: In her experience, the odds that the calcifications are cancer, based on what she is seeing in my mammographic images of Starbright, are 100 percent. She coughs. The cough reflects the fact that she's not comfortable lying. She asks, "Would you like a Kleenex?"

She's ready if I cry. Forty years ago, the New York Channel 4 newscaster Betty Rollin titled a book she wrote, First, You Cry. I read it when I was a kid because my father watches Channel 4 news, and he got it out of the library. He hid it, but I found it, no surprise there. Betty's book starts with her learning she has breast cancer and she cries. Then the reader goes on to find out the book is about how the diagnosis screwed up her life; a life that was already screwed up because her husband was a philanderer; but it was especially about how no one wants to talk about such an embarrassing subject as breasts (which is why my father hid the book).

In perfect timing, the book has been re-issued, a new edition. I will shortly read it again and come to realize it was a best seller because it was so good. It's not a book about cancer. It's no more about cancer than The Martian was about Mars. I tell you that because recently, publishers have decided people are sick of cancer books. They're not. They're sick of self-help books, especially the ones meant to help people with cancer. The help is pathetic and usually along the lines of advice such as: Dance like no one is watching you, or worse, Everything happens for a reason. What Betty's book is about is getting hit with one accurately hurled monkey wrench, dislodging her in a way that she finds herself in the middle of a crap shoot.

Life is full of flying monkey wrenches, isn't it? Like finding out your husband is a piece of shit the way Betty did. Like finding out you have breast cancer. First, You Cry is a story of dealing with the monkey wrench, and how your family and your friends deal with it, and how you deal with managing looking in the mirror, what with that big bump on your forehead staring back at you. (Metaphorically speaking.)

Betty's book, like all good memoir, is tragic but also exhilarating. It's why everyone reads them. (Nowadays, people use the word "redemptive" a lot instead of "exhilarating." Sorry but "redemptive" is too pop-religious. People are sick of redemptive books, along with self-help books, but they'll never be sick of memoirs.)

Warning: I'm hearing publishers are now saying people are sick of "domestic" books. Don't get me started.

Meanwhile, you remember my radiologist is waving Kleenex at me, right? So here's what I say to her, "No, thank you. I don't need a Kleenex." First, I don't cry. I say to her, "Listen, I am really pissed off. I need you to tell me what to expect."

She puts the Kleenex down and takes my hands in both of hers. "Please, please understand that if there are cancerous cells in your mammary duct, we have caught the cancer early enough to cure it."

I am apparently hallucinating. The doctor is telling me the cancer that is more than likely inside Starbright is curable.

She says, "Did you hear me?"

I say, "Yes. What do you mean by cure it? There is no cure for cancer. You die from cancer."

"Again, if you do have a cancer, it is at a stage where it is entirely curable."

I am trying to believe her.Here's how my mother describes her golf partner's stomach cancer: "They took him into the operating room and opened him up…loaded with cancer! Loaded! Sewed him right back together again. Left the damn cancer where it was. They'd've needed a shovel to get it out. Dead in a month."

Most ironically, my mother is diagnosed with stomach cancer shortly thereafter. They open her up—loaded with cancer. I picture a load of cancer looking like oatmeal. They take out ninety percent of my mother's stomach; treat her with a short course of chemotherapy; and she's back on the links in no time; but dead in a year. That's all the time chemotherapy can give her. Right up until her last month, she has a good year of doing what she loves—playing golf; replacing golf with cut-throat card games when there's snow on the fairways; getting her hair done once a week, hanging out with her sister, my Auntie Margaret; doing crossword puzzles; knitting sweaters; and watching Pat Sajak and Vanna White every day, no matter what. The last month? There can be no dignity in death, same way it is with childbirth.

Now I hold a short, silent one-sided conversation with my mom. I say: I tried my best, but I want you to know you were dignified in the way that you never referred to chemotherapy as chemo. Sometimes a nickname is not appropriate, I agree with you there. Don't let me need it, though, okay Mom?

The radiologist is speaking, still holding my hands, yet more warmly. It's hard to pay attention when you're pissed one minute and desolate the next. I still cannot buy "curable cancer." I think back; did she cough? I can't remember. I only know that of all the people in my extended family, anyone I know who had cancer was never cured.

Now she says, "If the cluster of cells is a lesion—something we won't know till we have the pathology report—then we have found a cancer before it can be felt, or even seen by the human eye. If there are cancer cells in the duct, your surgeon will excise the duct, and the cancer will never come back. Never. It can't come back. The duct will be gone, and the cancer along with it. There is no evidence of cancer cells outside the duct."

Even though I probably have a duct full of cancer, at least it's not a stomachful. I say to the radiologist what I'm next thinking. "Calcifications might show up in another duct next year, right?"

"No. After the lesion is disappeared by Dr. Quigley, your post-operative treatment will prevent any new cancer cells from developing in…the left breast."

I let that soak in. "Post-operative treatment is chemotherapy, right?"

"Not likely in your case since the lesion is minuscule. Dr. Quigley, and your oncologist, and your radiologist will discuss radiation with you. Also, any drug treatment to follow."

"You're my radiologist."

"I do not give radiation treatment. I—"

"Sorry, I forgot." I pause to drum up some courage. "But what are the chances that what I have is a more advanced cancer than what you…" How should I say this? "…than what the images are telling you? What are the chances you missed something?"

Now she pauses. Then, "I don't miss anything." Another pause. "But I have to tell you that sometimes, a protuberance—a tiny bit of a cell—will penetrate the duct wall. So tiny it will not be visible on the mammogram image. The pathologist will see it, though—once the duct is excised. Then you'll be scheduled for a second surgery but through the same incision. Dr. Quigley will take out a margin that incorporates any tiny bits of a cancer cell that might have worked their way through the duct wall."

Is this a horror film, or what?

I ask her, "What are the chances of that?"

"Twenty-five percent."

Another twenty-five percent. I might believe the statistic if she'd said twenty-two and seven-eighths percent.

She officially has no more time for me; she leans back out of my face, and says, "Let's go ahead and make that appointment for a biopsy, shall we?"

I'm suddenly exhausted. I can't ask her if there is anything else she should tell me because I've shut down. But not to worry. There are other people I will be able to question: this Dr. Quigley person; the oncologist; and a radiologist—one who actually does the radiating.

But my image-reading radiologist has one last thing to tell me: "During the biopsy, in addition to the little marker, they'll leave a chip in your breast so that in future mammograms we'll be able to zero in on the exact area of the excised duct if we have to."

Believe it or not, I say, "The vet put a chip in my dog's ear so they can find him if he ever gets lost or stolen."

She is glad to smile again. Broad grin. "Same idea, sort of. What's your dog's name?"

I tell her his real name in case she's a baseball fan. "Saltalamacchia." (Jarrod Saltalamacchia started his too-few years catching for the Red Sox the summer Salty was born. They both have curly hair as well as extraordinary catching prowess. My cousins, Patty and Meggan, called me from Fenway Park: "We snagged two seats in the loge box behind home plate. The curls are exactly the same!")

The radiologist, what with the expression she makes, is clearly not into baseball. So I say, "But we call him Salty."

She's a dog-person though; she remains curious. "What is he?"

"A labradoodle."

"Cool. He doesn't shed. How great is that? I have a beagle. We had to buy a really powerful vacuum cleaner a week after we got him. He's two."

I say, "Salty is two! What's your beagle's name?"

"His name is Greensleeves. Guess what we call him?"

"Greenie."

"Sleeves!"

Now we both laugh. I can't believe I laughed, but I did. She says, "I'll have Dr. Quigley's assistant call you. Her name is Beth. She'll make the appointment for the biopsy and another with Dr. Quigley, once they have the pathology report. At that appointment, Dr. Quigley will discuss the pathology with you, and take it from there."

I wish she'd left out the take it from there part. Laughing or otherwise, I'm in no condition to think about crossing a further bridge. She stands. So do I. She hugs me. I hug her back.

The hug softens the trepidation of what I am now thinking: I have to tell Charlie.

Once in my car, I take my ideas notebook out of the glove compartment and jot down what just happened in a nutshell. In 2006 I wrote a memoir, Girls of Tender Age. Maybe I'll write another one. If I pivot from taking notes to tackling a second memoir, I'll not only be writing a monkey wrench book like Betty's, it will be a love story too. And a dog story. And it will be in the immediate now, rather than the usual memoir configuration—the relating of a past event. Can you tell I'm dying to start?

Chapter 4.

I GO INTO THE waiting room where Charlie is sitting on a sofa all alone, looking into a magazine he's not reading. He doesn't hear me come in because he basically can't hear anything as soft as sneakered footsteps, even with the industrial-strength hearing aids he wears. Then he senses me. He's up and his arms are around me. After a moment or two, we sit down together.

I tell him everything except the one-hundred percent odds part that I detected in the radiologist's expression. I start with, "The doctor says that the mammogram found these strange cells in a mammary duct." I skip the junk moniker, too. "So, I have to have a biopsy to see if they're cancer cells. She told me they found them early enough so that if they do turn out to be cancer cells, the duct will be removed and I will be cured."

(Did you note the euphemism removed, instead of cut out? An example of why God created euphemisms.)

Charlie responds the same way I did. "Did you say cured?"

"Yes. A breast surgeon will take out the duct. But the radiologist says she's not seeing any cells outside the duct. Either way, when the duct is gone, the cancer cells will be,too."

I am unable to mention the possibility of cancer cell protuberances having successfully penetrated the duct wall before wiggling the rest of their sorry-ass selves out of there and onto a path of destruction. Nor am I in the mood to get into the margin thing. What comes into my head to rescue me from such dread? The movie we watched not long ago from Netflix.

When the new "The Blob" came out, we wanted to see the original. It was a 50s horror film about a small, round, half-solid/half-liquid ball that just happens to be in a meteorite, a meteorite that just happens to collide with earth; it's too small a crash for anyone to notice except by your basic town drunk, who just happens to be wandering the woods in the dark. He sees a flash ahead of him. (This is in rural Pennsylvania, a place James Carville once described thusly: Pennsylvania is two cities, Philadelphia on one end and Pittsburgh on the other. Everything in-between is Alabama.) The town drunk gets a stick and pokes the meteor. I won't tell you what happens to him before the little ball goes rolling out of the woods. Soon, it reaches a street, catches up to and devours one hapless soul after another, none of whom can outrun it.

Do I need to explain that the little ball gets bigger and bigger as it digests half the people in town? Are you seeing metaphor here?

The above flashback appeared and disappeared in moments because Charlie's intense gaze brought me back. I know he knows there's more to it than what I've said so far. I have no choice but to describe the possible cancer pieces escaping, but I also stress the radiologist's strong feeling that the chances are slim since she didn't see any, making the margin-removal possibility also slim, which I now bring myself to tell him about.

I'm glad I told him. He now has the radiologist's optimism going for him; God only knows what he was imagining.The relief on his face makes me see that even though I'm facing the possibility of bad news, he is also facing losing another wife to breast cancer.

When you feel love and affection for someone, even if it is mixed in with devastation, the desire to spit nails can be temporarily nudged off to the side of your brain. I touch my lips to his ear. "Kiss me."

He kisses me and then he says, "I'm sorry for all this. You don't deserve it."

We lean on each other for a bit, and then I have to say, "I'll be getting a call from someone today to make an appointment for a biopsy. So we have to get going."

"Okay."

I take his hand. Then we stand up.

During the ride home, I do what moms and dads do in crisis; we think about our children. I lean back and close my eyes. I think about our four.

Charlie's son Jay is getting married in three weeks. When Jay and I met, when we made eye contact for the first time, we liked each other instantly. Maybe because we're both artists and know the same struggles. He's a musician. His band is "The Pop Rocks." They play 80's hits. Did you like the 80's sound? Did you hate the 80's sound? Did you know there even was an 80's sound? Doesn't matter. If you see them, you find yourself singing along—blessing African rains, building cities on rock and roll, and celebratinggirls who just want to have fun. Queen's "Another One Bites the Dust," recorded in 1980, just makes the cut. Good thing—it always gets the crowd to dancing like one big whirling dervish. The band is—in the vernacular—awesome.

I had been excited about the approaching role—stepmom-of-the-groom—so determined to do Jay's real mother proud. But now this happens. I'm going to have to tell Jay and his bride-to-be about my mammogram. First I think I should wait till after the wedding to tell them, but no, I shouldn't. I can't use up all the stamina that would be required for me to lead a double life. A biopsy alone will take most of it, I can tell.

Jay's girl's name is Melissa. The first written mention of the word melissa is in an ancient piece of Greek writing. Melissa, in Greek, means honeybee. The name so fits her: lighter than air, and she pollinates everyone who knows her with her kindly grace. From the minute Jay and Melissa are engaged, it's pretty clear a fairy tale wedding is on the horizon.

My son Jere's wedding took place on an island a few months ago, just he and his Kim. They hopped on the ferry from Narragansett in Rhode Island where they live, and had their private and personal ceremony on the most beautiful spot on earth, Block Island. I didn't get to be mother-of-the-groom who walks down an aisle, but as it turns out, Jay will be my back-up.

Jere and Kim's wedding was another version of a fairy tale. After the ceremony, they had a reception for two—them. Instead of people, their guests were the millions of stars of the Delta Aquarids, falling all around them. But, unexpectedly, they did end up with one human guest actually: a witness was recruited, who turned out to be a star in his own right. The merry couple was no sooner off the ferry when they saw the comedian Steven Wright walking down the street. They are huge fans. (We all are.)

They stopped in their tracks, and Kim nudged Jere, who thought, This is it, and without giving himself time to chicken out, went right up to Steven, telling him how he and his girlfriend are crazy about him, giving him significant details as to that craziness, and that they are getting married in a few hours, and will he be their witness? Steven Wright had spotted Kim kind of hanging back while Jere was saying everything all at once. He smiled at her. She smiled back. I don't know which is more dazzling about Kim—her so-genuine smile; her huge, green Bette Davis eyes; her one-day-burgundy/one-day-chartreuse hair; or the 2004 Red Sox World Series Championship logo tattooed at the base of her spine just above the bikini line. (Steven is wearing his 1980's-era Red Sox hat when they spot him. Jere's own Red Sox hat is of the same era.)

Dazzling, too, her soap company, named after her two grandmothers: "The Stella Marie Soap Company"—every bar, divine.

So Steven Wright looked to Jere again and said, "Sometimes I have to think about things." All the same, he put Jere's number into his cell, didn't say, Don't call me, I'll call you, and Jere gave him the time and location of the wedding—eight o'clock that night on the sand at the foot of Mohegan Bluffs.

Back at their hotel, right when they're watching him on YouTube, a text message from Steven appears on the screen: I'll be there. A Block Island hotel is the kind of place where you can jump up and down on your bed, screaming with joy, and no one bats an eyelash.

Five minutes before the ceremony was to start, Jere and Kim watched their witness climb down the treacherous wood stairway zigzagging the face of Mohegan Bluffs to the beach 206 feet below, where they're standing with a game acquaintance who has a certificate to marry people in the state of Rhode Island, and his wife, a photographer. Steven Wright has to juggle his wedding gift while he makes his descent. It's a kite. This is what he says to Jere and Kim: "It's not meant to be flown. It's a symbol of your love taking off." I don't know if they got teary, but when they told me that, I did.

Then he witnesses them take their vows and signs their marriage certificate.

Jere and Kim will stay on the beach long after Steven, the officiate and his wife have made their way back up the bluffs. They await the blessings of the Delta Aquarids.

At approximately the same time, Charlie, me, and the rest of our family, are standing on a bluff above Long Island Sound, flutes of champagne raised in the direction of Block Island, and we toast our newlyweds. As my astrological sign is Aquarius, the constellation from whence the Delta Aquarids emerge. I felt free to beam the water-bearer a message, asking him if he wouldn't mind issuing more meteors than usual. He did not disappoint. I didn't get to go to the wedding, but the same meteors that the bride and groom saw streaking over their heads were the same ones streaking that came streaking over mine.

So lucky me: two daughters-in-law, Melissa, honey-golden, and Kim as Technicolor as the aurora borealis.

With all this wonderful dual wedding stuff, I really have a lot to be happy about, even though I know my anger will rise again. For now, wanting to believe I'll be cured if I have cancer, though doubting it if I do, I am still a thrilled mom/stepmom. So in case you've ever wondered if a thrill can be experienced, even when a person is devastated and in terror besides, the answer is yes.

Back home, Charlie holds a conversation with Starlight. While he gives Starbright's soon-not-to-be identical twin a massage, he tells Starlight that we will work together to get Starbright through this. To have someone conversing with your right breast is very funny. Then we make love and when we are melting into sleep, Salty sneaks up beside me. On this night though, he tucks his head into my left armpit and snuggles up to Starbright. All those stories about how a dog can sense a lot of stuff with his baseball-size brain are true. I do what I normally do—pat Salty's head, turn from him and snuggle closer to Charlie's back. But tonight, I first have to extricate my arm from under Salty's head. I whisper to him when I pat his head, "You're a good boy. I love you." And he is content to sleep against my back.

Not long afterward, Charlie stirs with the assurance that I'm asleep. I am, but I wake up when he creeps out from under the blanket because even with a king size TempurPedic, you can feel the other person get out of bed. He circles our giant bed that we are still paying for and gets in on the other side of our dog, who is doing his best to protect me from whatever it is he senses. Or maybe Salty knows exactly what's going on. Just because a dog doesn't speak your language doesn't mean he doesn't understand it.

Like me, Charlie realizes we now have a fourth partner, in addition to Starlight, who will help Starbright survive—our Salty dog. He puts his arm around both of us, and we fall asleep on a three-foot edge of a thousand-square-foot bed.

This is what makes me cry. Dog-love.

Chapter 5.

I AWAKE TO the smell of potatoes frying in onions and paprika. Smoked paprika. Have you ever tried it? Try it.

I awake perturbed, too, that I didn't get the biopsy call. I open my eyes. Charlie is not in bed. Neither is Salty. Charlie is in the kitchen and Salty with him having no doubt woken to the sweet sound of a package of bacon being unwrapped. Now I can smell the bacon frying too.

A couple of times a week, Charlie will wake up and say, "I need eggs." That's after he has one of those climaxes where he makes the noise of a herd of wild boar. I keep telling him we're going to get a knock on the door from the town's animal protection lady asking if we're harboring wildlife.

On this morning, he figures both of us need eggs; this has nothing to do with replenishing his sperm supply, but rather to replenish our spirits that are so crappily diminished. So here he comes into the bedroom with two Greyhounds. I sit up. In case you don't know, a Greyhound is grapefruit juice and vodka, preferably fresh grapefruit juice and preferably Grey Goose. We had our first Greyhound at Pepe's, the oldest restaurant in Key West, where the grill guy—a descendent of Pepe—makes a highly noted breakfast. I have to say, though, after a Pepe's Greyhound, you don't know what the hell you're eating. Or care. You only know it's really good. At first, I'd said to Charlie that I didn't know about drinking at ten AM, bhe guy next to me said, "If there's no vodka in my orange juice, I'll need an ambulance." So when in Rome… Charlie told me that after three sips of the Greyhound, I was blathering on to everyone within earshot that Pepe's oatmeal was better than even the oatmeal you get at the Dorchester Hotel across the street from Hyde Park. Charlie had to whisper to me, "I think this is Cream of Wheat. They must have run out of oatmeal."

Pepe's waitress overheard him. She said to us, "It's grits." I laugh instead of feeling like an idiot, what with the Greyhound.

Now, Charlie sits down on the bed, hands me my glass, and we clink. No toast, just the clink. What are we supposed to say? Here's to Starbright having a long life? We have a sip, and I realize that Charlie managed to run out to Stop & Shop and bought actual grapefruits to squeeze, a whole bag I'm sure, since he doesn't know how to buy fewer than six of anything.

I say, "Mahalo, Charlie." We learned to say mahalo instead of thank you in Hawaii. I always say mahalo after those aforementioned orgasms. Charlie says, "Aloha," which in addition to hello, also means you're welcome, and it means, I love you, depending on the circumstances.

At our second sip of Greyhounds, Salty appears in the doorway with a look on his face that says, "I'm getting really tired of waiting for my bacon." Then he trots back to the kitchen where he will return to his post, guarding the bacon until Charlie can attend to breakfast again, instead of to me.

Charlie gives me a smooch. "Five minutes, okay?"

"Okay."

I roll over for my five minutes. I'm depressed. I try to think about the beautiful dress for the wedding, hanging in the shop in Branford, waiting for me to model it for Melissa. But I'm unable to concentrate on a happy thought.

I sit up when I hear Charlie dishing everything out, telling Salty, "Go get the Mommy." (We refer to ourselves as The Mommy and The Daddy when speaking to Salty.) Salty gallops into the bedroom, jumps on the bed, and barks at me—Get up, get up! The bacon's done!

I throw off the covers, and he runs back to the kitchen in case the bacon is escaping. That cheers me a tiny bit. He's a handsome dog, our doodle. He's apricot. That's his color according to his breeder. She also says, "This puppy is happy in his own skin." We don't know what that means. It's my first dog and Charlie's second. He only had his first dog for a few weeks before it fell off the third floor porch in the tenement in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he lived. Charlie is convinced the landlord threw the dog down the stairs because the guy was a son of a bitch, always threatening to evict Charlie and his mother and brother. This is the kind of thought that takes over when you're depressed.

I put on Charlie's white terrycloth bathrobe instead of mine. I need a great big soft and cozy one. It doesn't warm me up. I drag myself out to the kitchen.

As we sit down to our breakfast, I am overtaken by the grief I feel for myself. Suddenly, I might as well be a banana peel tossed out a car window onto the side of the road. How will I eat Charlie's bountiful breakfast spread out before me? I have zero appetite. I'm getting more depressed with each second. Then I notice the little bowl of blueberries to the side of the butter dish, even though we aren't having cereal. The blueberries hit a nerve, one made really sensitive by my depression. I don't feel a ping of anger. Instead, this blast of fury fills me to the brimand is about to blow out the top of my head.

Charlie feels it. "What's the matter, honey?"

I'm staring at the bowl of blueberries. I look up at him and bash my fist on the table. Dishes rattle and glasses wobble. Salty jumps.

"HOW THE FUCK CAN I HAVE FUCKING BREAST CANCER? ME? ME! I DON'T SMOKE. I'M NOT AN ALCOHOLIC. I EAT RIGHT. I EXERCISE. MY MOTHER DIDN'T HAVE BREAST CANCER, SHE HAD STOMACH CANCER. I BREAST-FED TWO BABIES FOR TWENTY YEARS EACH, AND EVERY GODDAMN FUCKING MORNING I COVER MY GODDAMN FUCKING CEREAL WITH GODDAMN FUCKING BLUEBERRIES! THEY DIDN'T FUCKING WORK!"

I'm crying just the way Betty Rollin did when she got hit with a monkey wrench. I'm getting hit with mine yet again, but this crying isn't despair, it's fury.

Charlie is stricken, frozen in place, coffee mug raised, knowing what a terrible mistake he made putting out the blueberries.

When I was a child, my mother never complained. She'd say, "I blame the government!"

This was long before it was de rigueur to blame the government. I need Charlie to know right this minute that I'm pissed at the calcifications in Starbright's duct, and absolutely in no way am I angry with him for the blueberries. I raise my head from my arms folded on the table in front of me, sit back up, and say, "I blame the government."

His eyes close for a moment. I reach out and brush his cheek. Then he opens his eyes again. Damp eyes. I have managed to smile, don't ask me how. He breaks into a smile, too, a little one. Did I mention he has dimples? He knows I forgive him for trying to cure the cancer we both know I have with a bowl of blueberries. I don't need a phone call about the biopsy. I don't need a biopsy to tell me I have cancer. Neither does Charlie.

He puts his mug down. It's a souvenir from the duck boat tour we took in Boston. Our goofy picture is on the goofy mug. We are standing in front of the goofy duck boat. We were different people then. From now on, I'll be categorizing every event as "before monkey wrench" or "after monkey wrench": Duck boat tour, before; Jay and Melissa's wedding, after.

Salty barks. When he's distressed, he has this loud, sharp bark that sends piercing notes into Charlie's hearing aids. Charlie winces. Salty is distressed about my shouting, but he's also distressed since neither of us is passing him pieces of bacon anymore. He's been waiting at least two minutes, or ten years, he doesn't know the difference.

Charlie gives him an entire strip of bacon. Salty is so happy, he runs off to eat it in his favorite snacking spot—the middle of our Turkish rug that cost a shitload of money and is already spotted with the remains of Salty's favorite treats. I'd bring the carpet to be cleaned, but the last time I did that the expert in the cleaning of such rugs scolded me because there were cat hairs in the rug. (I had two cats at the time.) "You should never let a cat into a room with this quality a carpet." I really have to find a new guy.

Charlie says to me, "I love you, Wonder Woman." He calls me that sometimes.

I tell him I love him too, but new tears spill on down my cheeks. I say, "I really blame the luck of the draw."

"I'm sorry."

I don't let up. "It's a crap shoot, isn't it?"

"Yes, it is. C'mere." He pushes his chair back and puts out his hand. I take it and am drawn into his lap. He enfolds me. Incredibly, he says, "There's always a monkey wrench in the machinery."

I say into his chest, "Cancer is the worst monkey wrench."

Chapter 6.

BEFORE I MET CHARLIE, before I met anyone, my daughter encouraged me to get out there. She pointed out there were very few single men wandering about the condominium complex where I live. There are three, actually, and none appeal, though I do like a fellow named John quite a lot, who is half my age. He is cute and polite and kindly, and an Olympian besides. That would be a Special Olympian. He wears his several medals with pride, but he can't really say which competitions he won. John is afflicted with Down syndrome. He is also a baseball fan and we talk baseball. Our conversations are usually along the following lines based on my wearing a Red Sox hat and John wearing a cap of another color:

John: "I don't like the Red Sox."

Me: "Yankees Suck."

John starts singing "New York, New York," so I sing "Sweet Caroline," at the same time.

One day, John is wearing a new medal. I gush and then I ask John for his autograph, but he can't write. So I give him a stick and we walk down to the edge of the sound and he writes something with the stick. I take a picture of what John writes, which are not words of any known origin.

My relationship with John is not really going anywhere but he's a good friend.

Meanwhile, once it was four years since Charlie lost his wife, his own daughter told him what my daughter had recently told me—he had to get out there and meet people. At this time in his life, Charlie preferred being with his camping friends, Bruce, Gary and Jim, who he met through Cub Scouts when they were young men with small children. The four of them signed up to go the first camp-out. They were required to attend a meeting to learn how to deal with seven-year-olds, likely away from home alone for the first time. They figured they already had a handle on that so they didn't pay too much attention. That night, within an hour of lights-out, several boys were crying. The loudest was Charlie's son, Jay. The four dads didn't remember what they were supposed to do if a bunch of kids were all crying at the same time. The conversation they had went something like:

Gary: "Did anybody bring any weed?'

Bruce: "I got a bottle of Seagram's."

Jim: "Shouldn't we first see why those kids are crying?"

Charlie: "They'll probably fall asleep."

They didn't.

Charlie and his friends decided to juggle the sleeping arrangements and put the weepers all in one tent. Charlie volunteered to sleep with them since his own son was making the most noise. He spent the night squished amongst seven-year-olds who wanted to go home. Charlie told them, as soon as morning comes, we'll go fishing, how's that? The only thing is, first you have to stop crying so we can get some sleep. You can't catch fish if you're tired."

They settled down. Charlie snuck out, and played cards with the three other dads, drank, ate brownies that one of the wives sent in case the boys couldn't sleep—they forgot about the brownies till the kids were asleep. Jay told me his dad was the best dad for getting stuck sleeping bag zippers unstuck and for untangling fishing lines. Charlie told me that the first year camping with the boys it was all he did.

The boys lost interest in scouting about when they entered middle school. They'd come to prefer events where girls were part of the proceedings. But the dads continued the tradition of a yearly, week-long camp-out—fishing most of the day, then grilling their fish in the fire after having released all but what they'd eat. Do you know there's a release fishing hook with no barb so that the fish can just release him or herself without help? The foursome would bring a lot of food from home since they couldn't live on fish, and Charlie volunteered to cook. Bruce brought Seagram's, Jim, his guitar and harmonica, and Gary, a stash of weed. They continue to honor this tradition.

Anyway, Charlie's daughter Kristin, and my daughter Jene, push eHarmony. Jene gets me the form online and I fill it out, what the hell? Charlie felt he still wasn't ready. Kristin said to him, "You're ready, Dad," and took the bull by the horns. She filled out his form. We had to send along two photographs. I chose to send a black and white by the famous photographer, Marion Ettlinger, who does author portraits. (Her first published portrait was Truman Capote.) I'd written seven novels by then. When my memoir went to Simon & Schuster, I didn't pick a snapshot by a friend for the back cover; I spent six hours in Marion's studio. She contorted my body into many positions, seeing to my being sprawled across pieces of furniture draped with heavy fabric, while she fed me things like chocolate-covered strawberries and espresso candies; passed me glasses of wine; and played a variety of music—classical to hip-hop. At the end of the session, I had to take a taxi to Grand Central because I was having trouble walking. My back hurt, my neck hurt, my elbows and knees hurt. In the taxi, I glommed down Advil.

My Marion Ettlinger portrait has been my most prized possession ever since.

In contrast with the brilliant Ettlinger, my second e-Harmony picture was taken at Fenway Park after my son and I were in line for a long time in order to have a picture of us posed in front of the 2004 Red Sox World Series trophy at Fenway Park. It was 95 degrees and I was wearing shorts, a loose tank top with no bra, and my Sox hat. The guy behind us in line took the picture. I asked Jere when we picked up our pictures if it looked like I wasn't wearing a bra. "No," he lied.

The first four men I met through eHarmony were about the biggest assholes I've ever come across, the last an economist, who bragged that he was responsible for pharmaceutical ads being allowed to air on TV. I said, "Wow…because of you I get to see two people sitting in separate bathtubs out in a field, no plumbing in sight, holding up wine glasses, and obviously about to have ravenous sex after the guy's Viagra kicks in."

The economist was not amused. Also, he'd positioned himself at a table where he could stare at any and all woman who come through the door. I was not amused, which is why I told him I was in labor and had to leave. He didn't hear me since he was concentrating on some teenager's butt. I got up and put my coat on. He noticed. He said, "Where ya goin'?" I said, "My water just broke," and escaped.

I went home and wrote. I'm fortunate to have such a refuge. I called Jene when I got home and told her I was closing my eHarmony account. She sympathized and apologized for pushing me and I told her I could have said no, that it was hardly her fault. Before I went to bed, I checked my email, and while I was reading one, a new one popped up. From eHarmony. A picture of a guy on a boat: Meet Charlie! Nice boat. Hydra Sport: two Evinrude 250 engines. Couldn't really make out the guy too well. Didn't matter. I live on Long Island Sound. I'm a water person.

The clever Kristin had seen to a second picture—her father holding a baby. He's wearing a suit. I guessed the picture was taken at the baby's christening. They are nuzzling each other. His little essay was direct. I have been a widower for four years. It has been a sad time. But we've got a new baby in our family. Then there's a third picture, again on the boat, with the baby asleep in Kristin's lap, her husband, Mike, and her brother, Jay. Charlie is flipping hamburgers on a little grill attached to the back of the boat; they are already eating the first round. This Charlie has a spatula in one hand and a burger of his own in the other.

So, okay, I'll try one more of these guys. He doesn't look like a jerk. The other ones did, I have to say. And so, they were. I'll get a boat ride out of it. Also, Charlie's an engineer. If the boat engine conks out in the middle of Long Island Sound, presumably he'll be able to fix it.

First though, I had to go through the eHarmony drill. I have to send the guy on the boat a response. A guy who is mourning his late wife; has a baby in his life who appears to have made him happy; and a son and son-in-law who don't look like jerks either. I have to pick three questions chosen from eHarmony's "Getting to know you" instructions: questions like, What kind of music do you listen to? You have the option of asking something original. Before I list my choices I write, I'm sorry for your loss. You must miss your wife. Then I got on with it. I picked one of their questions; I was tired. What is your idea of a great Saturday night date? After the first four flops, maybe this boat-owning engineer would choose something other than, Go to a movie. I don't want to see movies with strangers. How do you get to know someone when you can't talk? I was thinking more along the lines of: Go for a walk along the Sound and then get an ice cream cone, though that probably sounds like a metaphor for Cinderella singing that someday her prince would come.

I read his answer the next morning while I was drinking my coffee. I put Gail Collins's column aside. All I can say is that it was quite the variation on what I was looking for. He starts with: Thank you for your sympathy. Then he gets on with it:

My idea of a great Saturday night date would like to have the person come to my house so I can cook her a great dinner. Maybe lamb chops on my grill, or tequila chicken. I'll make her favorite drink so that, while I cook, she can lounge on my deck. Then when everything is getting close to done, I can go out and chat with her. After dinner, I'll put on some music and we can dance. Slow dance. Then we have great sex, and in the morning we'll go out for a big breakfast, hopefully after more great sex.

I am so impressed with his blatant honesty. Impressed with the implication, too, that he has been moving on since his wife died.

I respond with: That would be my idea of a great Saturday night too, but only after I come to like the guy really a lot, and mostly, feel I can trust him.

Does that sound like a resounding, Sayonara?

Charlie doesn't interpret it that way. He writes, Can we skip emailing and just go get a cup of coffee?

I write back, That's where my four other eHarmony get-togethers ended. I couldn't get past the coffee. Just so you know.

He writes back, I wish that's where my eHarmony get-togethers ended.

But yet, we keep writing back and forth. By the time we get around to finding a date to have coffee, he writes, "Maybe we can get breakfast? You can choose where."

I love going out for breakfast, especially to diners. I choose a diner between him and me. We decide a week from Sunday.

With more email exchanges, independent of prescribed eHarmony questions, I learn that besides being a widower and having a new baby in his family, he's an engineer at Sikorsky.

I ask, What sort of engineering do you do at Sikorsky?

I've just finished a project going over safety issues on Marine One, the President's helicopter.

I ask, Is the President now safe?

Yes. The only thing that needed to be improved was the one-inch step down from the ramp-door to the door-ladder.

Me: The President has to climb down a ladder?

Him: It's called a ladder, but it's a stairway.

Me: Did that get done?

Him: Yes. Now where the two meet, it's level.

Me: How did you do it?

Him: We redesigned the fuselage so that the door opening is an inch higher.

Wow. I have to say that would seem rather a round-about way to fix the door problem. I don't question him further, though I'd like to because I'm a curious person. At the same time, I'm able to call up my sensitivity when I'm about to be a pain in the ass.

In the Times the next morning I read an article about how marriages work best wherein the two partners teach each other things all the time. I surely liked learning how to level the stair from a helicopter with the fuselage.